For more than a hundred years, the aqueduct at Landsburg Park near Maple Valley was the end of the line for salmon in the Cedar River watershed. Built between 1899 and 1901 through a voter initiative to provide water for the city of Seattle after the great Seattle fire, the water system is the envy of municipalities all over the country. Two-thirds of the water supply comes from reservoirs that are surrounded by mountains and pristine lands, many of which were once logged but are now largely untouched by human civilization.

The area above Landsburg Dam is some of the best fish habitat in the region. But like so much infrastructure built at the turn of the century, its construction did not take the needs of fish into account.

“Both in 1901 and again in the 1930s when the dam was built into its present state, we didn’t account for passage for migratory fish,” says Michele Koehler, a senior fish ecologist with Seattle Public Utilities, which operates the Landsburg Dam. Koehler’s work is part of the utility’s Habitat Conservation Plan. The 50-year plan was prepared under the federal Endangered Species Act, which listed Puget Sound chinook and several other species of local salmon as threatened species in 1999.

Fish Face ‘Interrogation’ By Technicians At Pescalator

Until 2003, when a fish ladder was installed by the utility, the waterworks blocked fish passage. Koehler says fall runs of returning salmon would get stuck at the aqueduct crossing below Landsburg Dam and spawn there in large numbers in less than ideal conditions.

Now, the fish ladder allows most species to get past the dam. But first they have to swim through something called the “Pescalator” and face what Koehler calls an “interrogation” by technicians.

“We don’t check their passport or anything like that,” Koehler jokes as she stands near the conveyor where fish come through.

The Pescalator is a two-and-a-half-foot-wide spiral that slowly turns, gently carrying fish and water from a holding pond at the top of the fish ladder up onto a sorting table.

Technicians there measure the length of most of the fish as well noting their gender and whether their adipose fin is clipped, which would indicate that they come from a hatchery.

“And then also for chinook salmon, we take a piece of genetic material, a fin clip, so that can be used for DNA analysis and to look and see if these fish are producing offspring or not,” Koehler says.

The data is used to track recovery efforts under the Endangered Species Act.

Impact On Water Quality Not A Problem

Coho and cutthroat trout are also allowed passage above the dam, because the utility has determined their numbers are small enough not to impact water quality. But Koehler says the large numbers of sockeye that arrive at the Landsburg fish ladder could be a problem.

“Sockeye salmon can show up and do something called mass spawning,” Koehler says. “Mass spawning could result in a pulse of nutrients from all the carcasses decaying at once, which could negatively impact the drinking water quality, whereas chinook and coho and other species we put above the dam aren’t likely to be as numerous and they spawn, especially coho, over a much longer span of time. So we’d be less likely to get a pulse of nutrients.”

And even in a great year for salmon returns, Koehler says it’s unlikely that any of the allowed species, especially chinook, would come back in numbers large enough to pollute Seattle’s water.

“We have never come close to impacting the water quality with the number of carcasses that have [shown up] past the dam so far,” she says. “We’d need to be in the thousands and thousands of fish before we reach that point.”

After The Pescalator, A Resting Place, Then ‘Shangri-La’

Most of the sockeye come from a nearby hatchery, which was built in conjunction with the fish ladder. So as part of the habitat conservation plan, the sockeye are held in tanks and taken from the dam back to the hatchery, where their lives begin and end.

The rest of the fish are hand-carried a couple hundred feet in rubber tote bags full of water to a deep pool upstream of the dam. There, they can recover for as long as they like in still water from the trials of the fish ladder and being handled at the Pescalator.

Then they’re free to swim into the remaining 21 miles of habitat on the Cedar River upstream of the dam. The natural barrier at Cedar Falls is the highest point the chinook might reach before they spawn and die.

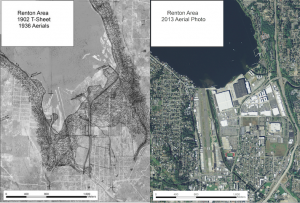

“In fact, we kind of call the habitat above the dam a Shangri-La,” Koehler says of the Cedar River Municipal Watershed, which is a 90,000-acre drainage owned by the city of Seattle and managed solely for water quality and conservation.

“Especially given that these fish have swum all the way through the very urban Seattle metropolitan area, once they get up here, they might kind of be breathing a sigh of relief,” Koehler says. “Not to personalize it too much, but it’s a different habitat up here. It’s not impacted by deforestation and urbanization, and dikes and levees and things like that.”

- Here’s the exterior of the Pescalator. (Bellamy Pailthorp/KPLU)

- The Pescalator sends the fish sliding down a chute. (Bellamy Pailthorp/KPLU)

- Awaiting technicians grab the fish. (Courtesy of SPU)

- Technicians examine the fish. (Courtesy of SPU)

- The fish are released into this resting pool. (Courtesy of SPU)

- And at last — salmon Shangri-La. (Bellamy Pailthorp/KPLU)

The Data Tells A ‘Success Story’

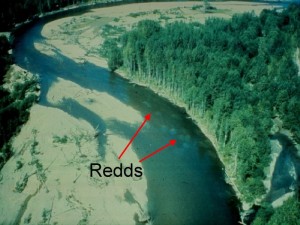

Data collected at the dam as well as surveys of salmon nests in the habitat upstream show the fish ladder is contributing to chinook recovery. Researchers at the University of Washington, NOAA Fisheries and the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife have all collaborated with Seattle Public Utilities to study the dam’s effects. The fish seem to do well once they get past Landsburg Dam.

“At first we were asking questions simply about recolonization. How successful are these fish when they move above the dam?” Koehler says. “But by sampling genetics year after year, after year, we started to get what’s called a parentage analysis, which means we can trace the offspring back to parents that we also sampled genetics from.”

The data shows that the fish that spawn above the dam produce offspring that also return to the dam, which Koehler calls “a good success story.”

This year, Koehler says researchers are also contributing to a study looking at the number of offspring produced between hatchery and wild chinook.

“Because we do have some hatchery fish that stray up here to the dam … it’s an easy spot to sample all of these fish and learn what we can about how many offspring each female chinook produces given her size, and her age, and things like that,” she says.

A Hopeful Trend Despite This Year’s Low Count

To an outsider, the fish ladder might seem like a daunting final gauntlet for the fish, says Koehler, even though research shows it’s a pretty safe and effective way to ensure fish passage.

“But all salmon have to run the gauntlet,” Koehler says. “I mean, they’re literally swimming upstream, and unfortunately that has become a metaphor for salmon recovery now.”

The year 2014 is shaping up to be a very low year for fish returns on the Cedar River, especially chinook. On the day of my recent visit, none of the mighty fish also known as kings came through; I saw only a handful of sockeye and one shimmering trout move through the Pescalator.

“But we have seen chinook over the last few days, so you know there’s just variability in how they move throughout the river,” Koehler says.

And as of Oct. 18, she says 198 chinook had passed through the fish ladder at Landsburg Dam (25 female and 173 male).

“That’s about in line with what we expected, given that the counts at the Hiram M. Chittenden Locks were low this year,” she says.

Experts say there is always a lot of natural variability in salmon returns. In addition, a flood in January 2011 is thought to have hurt this year’s cohort of spawners. And an accumulation of exceptionally warm water off the West Coast has been pushing many salmon into the colder waters of British Columbia.

“In the past we’ve had as many as nearly 400 chinook salmon. But in the early years after the fish ladder was opened, we really only had 50 t0 75 fish every year,” Koehler says, adding given those numbers, seeing nearly 200 show up at the Pescalator this year is a good sign. And data since 2003 show a slow upward trend that, along with visible habitat restoration, gives her hope.

“I have, first-hand, seen the resiliency of chinook salmon. And they are a mighty, beautiful, amazing creature,” Koehler says. “Despite all the odds, they’re still coming back to the Cedar River year after year, after year.”

Scientists estimate about 10 percent of the Cedar River run typically makes it to spawning ground above the dam. “Give or take,” Koehler says. “And of course we’d like to see that number go higher over time.”

She says a lot can be learned by looking at this run of fish, as it swims from the ocean, through the pollutants of Puget Sound, into the temperature trials of the Hiram M. Chittenden Locks and the Lake Washington Ship Canal, through Lake Washington and finally home to spawn on the Cedar River. She’d like to see more work on connecting habitats that are restored enough to help the fish survive, throughout their lives.

“The fish are only up here in this pristine environment for the end of their lives and beginning of their lives,” she says. “There are so many impacts to the rest of their lives that we need to make sure that we are taking care of their other life stages with our restoration. And we’re doing good work on the Cedar River and the Lake Washington basin, but we have to keep it up.”

Threat Of Climate Change ‘One Of The Hardest Things To Grapple With’

Koehler expects the recovery of endangered species to take a long very long time.

“I mean, I’ll be happy if I see it in my lifetime,” she says. “We’re making steps in the right direction, but really here at the Landsburg Dam we’ve only seen five or six generations of chinook salmon. And think of how long it took the salmon to decline — you know, decades and decades. So we are just embarking on this.”

At the same time, she says there’s the looming threat of climate change, which could very quickly undermine all of those efforts.

“It’s a big deal,” she says. “It’s one of the hardest things to grapple with.”

And there is a lot to consider, from how warmer water and more acidic oceans might be affecting the ocean food web, to the warmer temperatures it can cause in the lakes and rivers where salmon spawn.

“These fish might be subject to a much larger issue than even their specific habitat. And I think we’re starting to understand that but we don’t understand the full complexity of it,” she says. “And in my opinion, we’re not doing enough on that yet, and it’s going to impact resources we care so much about in the Pacific Northwest, like our chinook salmon.”