About five miles from the clogged freeways, shopping malls and airplane hangars at the south end of Lake Washington, the Cedar River starts winding its way through Maple Valley.

It’s here, along some 30 miles of streambeds, some just a few paces off the highway, where life begins and ends each fall for hundreds of Lake Washington chinook.

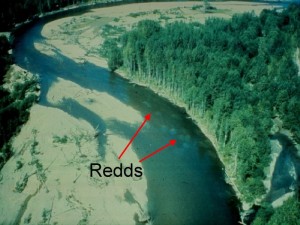

The land adjacent to the riverbed is undeveloped. Water flowing at just the right speed and depth over gravel that’s protected by a shady forest makes this habitat ideal for the spawning nests, called redds, that salmon create. A trained eye can spot them in an instant.

‘She Turns On Her Side And Uses Her Tail Like A Fan’

Karl Burton, a fish biologist who keeps track of salmon redds on the Cedar River for Seattle Public Utilities, says you can see the spawning nests by looking for differences in the color of the rocks that females turn over with their tails as they dig them.

“It’s usually a grey or bluish color, as opposed to a green or brown of rocks that are covered in algae,” Burton says. A spawning female also changes the topography of the river as she digs the redds, which are often about 6 feet wide and up to 30 feet long.

“When she moves in, she turns on her side and uses her tail like a fan to beat at the gravel and dig,” Burton says. In this way, the female fish works her way upriver, creating indents and mounds in the riverbed where she lays her eggs while a male fish swims alongside and fertilizes them.

To an untrained eye, an easier way to find spawning fish and their nests is to look for the white tails of the females.

“The tail tissue gets rubbed off on the rocks and by the time she’s done digging the nest, she’s basically removed all the tissue from her tail. And it’s really nothing but the bone structure of the tail and it turns white,” Burton says.

The females remain near their nests, guarding their territory from other spawning females anywhere from four days to a couple of weeks before they die.

And even though they are technically dying as they procreate, using all of their physical resources to produce offspring, their final sacrificial act is also a display of tremendous strength and power.

“The vast majority of their biomass is muscle. They can move rocks that are 6, 7 inches in diameter,” Burton says. “They’ve been in the ocean feeding for years, building up that muscle. So when they enter freshwater, even though they don’t feed, they’ve got muscle and they’ve got fat to live off of while they spawn.”

Changing Colors and Growing ‘Shark-Like Teeth’

The process of digging the redd as the fish spawn usually takes two to four days. It’s an amazing process to observe, says Burton, who has been tracking chinook for the utility for about 16 years now. Particularly fascinating to him is how quickly their bodies change as they mature and get ready to spawn.

“The fish are changing colors. Their bodies are elongating. They grow these large teeth; they almost look shark-like,” he says. “They also grow a hook on the end of their upper jaw, which is called a kype. And that kind of makes them look even more vicious.”

But as a fish biologist, Burton says he finds the whole process “absolutely beautiful.”

“I never stop getting excited about looking at spawning fish,” he says. “They keep me alive and they keep me motivated.”

Fighting Against The Odds

The spawning males use their fang-like teeth while chasing each other and competing for females. The females use them to guard their redds against other females, who are also looking for ideal places to spawn.

This transformation begins when they enter freshwater at the Hiram S. Chittenden Locks and takes place “in a matter of weeks,” Burton says.

“Once they get in the rivers is really where the biggest morphological changes occur,” he says.

And all the while, an average female lays about 4,500 eggs in each redd. How many fish ultimately emerge depends on incubation conditions, Burton says, but it’s generally just a few hundred. Predators, disease, bacteria and siltation that cause problems with oxygenation all play a role.

Flood danger is also a big concern. Water that flows too quickly can wipe out developing juveniles. Low flows also pose a threat, which is part of why Burton tracks the redds. His maps and measurements help ensure that the city of Seattle doesn’t take too much when it pulls drinking water from the watershed. About two-thirds of Seattle’s drinking water comes from the Cedar.

Despite A Low Year, An Optimistic Outlook

This year is a down year for Cedar River salmon in general. Initial counts at the locks indicate it’s shaping up to be the second or third lowest year for Lake Washington chinook since counting began in 1995. Burton thinks one big reason for that is a flood that occurred in January 2011. He says returning salmon are usually predominantly 4 years old, and the flood likely wiped out many of what would’ve been this year’s fish before they hatched.

“I think that had a major impact on that cohort of fish,” he says. “They were in the gravel when that flood occurred and I’m sure there was a very high mortality rate due to the high velocities.”

But Burton is generally optimistic about the efforts he’s a part of and the effects of conservation work dictated by the federal listing of chinook as a threatened species 15 years ago.

“It’s very difficult to link specific efforts to recover fish to an increase in abundance … Salmon abundance naturally is very dynamic,” he says. “But in terms of the chinook salmon, I think there is evidence that we’ve had some improvement. If you look at the last 10 years, we’ve had two years where the chinook salmon has exceeded the escapement goal.”

Escapement goals are the survival rates set by the co-managers of recovery efforts, the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife and the Muckleshoot Indian Tribe.

“And the last time we exceeded the escapement goal was in the 1970s,” Burton says.

Habitat Improvement Helping Salmon’s Long Recovery

This year, they’re seeing a very favorable response to a habitat restoration project on a part of the river known as Rainbow Bend, where King County and Seattle Public Utilities bought property and removed levies to open up 40 acres of flood plains. This provides a more flexible shoreline and allows the fish access to side channels when flows get too high for them. Burton says the work is very important.

“One of the major problems in this river in terms of survival is its disconnection from the flood plain,” Burton says. The large rock walls and levies that humans have installed to keep the Cedar from migrating also cut vulnerable juvenile fish off from places of refuge in side channels where they can find slower water velocities.

“When you put in levies, you’re basically cutting off the river’s ability to produce those types of environments and habitat. So the extent that we can remove those levies, it will definitely provide benefits for juvenile chinook,” Burton says.

And he says the surveys his team has completed in recent weeks document there are already eight chinook redds in a new side channel at Rainbow Bend.

“That’s almost 10 percent of the redds in the river at this point, so obviously, they must like something about the spawning habitat in that area,” Burton says.

Buruton thinks continued habitat improvement will help fish recover more in the future.

“Removing levies, adding large woody debris, planting native plants — [we are] trying our best to remove some of the development in the flood plain,” he says.

But he also thinks it’s very important to remain positive and remember that it’s been hundreds of years since Europeans showed up here and salmon runs started to decline. Fifteen years since the listing of Puget Sound chinook is a drop in the bucket, especially since the science of habitat restoration is so young.

“Trying to mimic nature is very difficult. Everything is interrelated and interconnected, and we don’t have a good grasp on all those connections yet,” Burton says, adding we should not expect depleted populations to bounce back quickly to a level we would consider a recovered state. “But if we can just be patient, learn from our mistakes, I think we’re headed in the right direction.”