One of the most intriguing questions about Lake Washington chinook is the mystery of how they survived after we replumbed the region with the construction of the Ship Canal, which was completed in 1916. It dropped the level of the lake by nearly 10 feet and cut it off from what used to be its southern outlet, the Green River.

After Replumbing, Salmon Prove To Be ‘Remarkably Resilient’

“The Cedar River used to flow out to Puget Sound through the Green River and the Duwamish,” says Kurt Fresh, a fisheries biologist with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration in Seattle.

Now it flows into the south end of Lake Washington in a small park in Renton, just beyond the lakeside hangars where Boeing builds its 737s.

“So this is not where it would naturally have entered Puget Sound,” Fresh says, looking across the lake toward the river mouth from the shoreline at Gene Coulon Park. “We diverted it.”

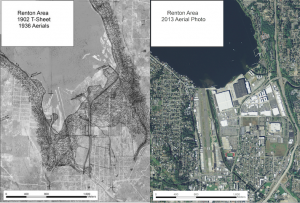

What’s more, we’ve also gradually paved over and developed the flat areas at the south end of the lake that were once wetlands. So fish that spawned on the Cedar River before the diversion then headed out to the ocean likely had trouble finding their way back as maturing adults three to five years later.

“Because if you were a chinook spawning in the Cedar River in 1915, you would have had to have found the new route,” Fresh says. “And there’s no data from that era, but it would have been really interesting to have seen how long this took.”

But clearly, the fish adapted to this change. They now find their way back through the Hiram M. Chittenden Locks and the Lake Washington Ship Canal, where they face the shock of a huge temperature change as well as low oxygen levels as they move into artificially shallow water that averages 72 degrees Fahrenheit when they arrive.

“Salmon are remarkably resilient. We keep giving them our best shot to knock them out and they take it and keep coming back,” Fresh says.

The fish have also evolved to fit the circumstances of all kinds of different landscapes and migratory paths they follow as they travel through life cycles that take them from freshwater rivers out to sea and back, sometimes covering thousands of miles.

“It’s really temperature and dissolved oxygen that are the things that we would be most concerned about,” says Fresh of his role as a federal research scientist, looking at conditions that affect chinook survival. “Because too high a temperature can kill the fish. Even if it’s not high enough to kill them, it can stress them and affect their ability to reproduce. And if you get dissolved oxygen levels low enough, it can kill fish.”

Swimming Off Their Fat While Smelling Their Way Home

Fresh says tagging data collected by NOAA and the Muckleshoot Tribe suggests that once the chinook start moving after passing through the locks, they often move very quickly through the Ship Canal and the lake, needing as few as a couple of days to reach their native spawning grounds. Depending on the year, it can also take a few weeks.

This file image shows adult fall chinook salmon. (Courtesy of Pacific Northwest National Laboratory)

“They’re not feeding by now,” he says. “They’re basically just sort of holding, swimming, burning off their fat.”

The fish find their way primarily by smell as they mature, getting ready to spawn.

“They have very sensitive noses and they navigate by smell, picking up fine chemicals in the water that tell them when they’re getting close to their natal stream,” Fresh says.

They also take cues from the weather, sensing drops in barometric pressure that trigger them to move and time their arrival with rains that will add water to their rivers and provide the most favorable conditions for spawning.

“A fish is trying to get to its spawning ground at the right time,” Fresh says. “And one of the right times is when there’s enough water for it to spawn in.” So, he says, they time their arrival when it’s raining and when the stream comes up in flow.

“Quite often, the farther they have to migrate up into a system, the more likely we see them move on barometric pressure,” Fresh says.

‘It’s Basically Dying Slowly’: The Maturation Of The Chinook

While in the lake, each fish undergoes a physiological revolution as it moves from saltwater to freshwater.

“It’s basically dying slowly,” Fresh says. “It’s sort of shutting down physiologically, putting as much of its energy into spawning as it has.”

The life cycle of salmon is part of what makes it so iconic. The instinctive drive to push through all kinds of obstacles to make it home and reproduce, despite fatal consequences, creates an almost mythical story of ultimate sacrifice.

“The fish is now focused on one thing: spawning,” Fresh says. “If you’re a female, you get those eggs in the gravel. If you’re a male, you fertilize as many eggs and females as you possibly can. And every ounce of your being is focused on doing that.”

In its final weeks, he says the salmon draw on blood and muscle tissue to stay alive and get to their spawning ground, where they defend their eggs as long as they possibly can.

“And then you die,” Fresh says. “All salmon die. This is the end of the line.”

A Keystone Species Responsible For More Than 137 Others

Yet that death earns them status as a keystone species, because of the beneficial way that their demise delivers biomass and nutrients back into upriver ecosystems.

“They are like the connecting tissue in our bodies. They connect the marine landscapes with freshwater and they connect freshwater with marine systems,” Fresh says. “You know we might not like smelly salmon, but as those fish decay, the nitrogen and phosphorous get incorporated into the plants in the system and fish get dragged into the bushes, where they die and actually act as fertilizer. Bugs eat them, their eggs and the carcass can be eaten by small fish.”

A report released by Washington’s State Department of Fish and Wildlife in 2000 found that more than 137 species depend on Northwest salmon for their survival.

“So they’re incredibly important,” Fresh says.

Adapting To The Changes We Made Before We Knew What We Know Now

But back around the turn of the century, when we eliminated the majority of their habitat, we didn’t yet understand that role, Fresh says, or how the loss of salmon habitat that resulted from construction of the Ship Canal could dramatically reduce their numbers and push them to the brink of extinction. Puget Sound chinook are now protected under federal law; they were listed as threatened under the Endangered Species Act in 1999.

This 1903 photo shows the Lake Washington shoreline. (Seattle Municipal Archives

Photograph Collection)

“In 1916 to 1918, we didn’t know as much as we do about salmon, so some of the things we’ve done in the past, probably we would be really reluctant to do now,” he says.

For example, he says we might not have eliminated so much of the wetlands that the fish depend on, directly and indirectly. The marshy landscapes act as giant filtration systems, keeping water clean. And they produce food that salmon or other creatures in their food chain eat.

Even without the wetlands, Lake Washington chinook have adapted. They use the shoreline of the lake for some of those same functions, especially in areas that are close to the river mouths where they come from. In winter, from approximately January to March, you can see juvenile chinook rearing in sandy beaches like the ones near the piers at Gene Coulon Park.

“They migrate downstream and they filter out into the lake,” Fresh says, working their way through the shallows and feeding on insects and other organisms that are produced in shallow shoreline areas.

“It’s really cool to see the fish as they swim along the shoreline here,” he says. “You can just stand on these docks and watch them.”

Homeowners with waterfront properties can also help more fish survive by creating conditions in which they thrive. King County has a green shorelines program to support fish-friendly improvements, such as the creation of beach coves and removal of concrete bulkheads and other armoring.

Lake Washington: ‘One Of The Great Success Stories’

Fresh also finds hope when considering how much people have done to improve water quality in the lake over the past 50 or so years.

“Lake Washington is one of the great success stories in terms of combatting pollution,” he says.

A generation ago, it wasn’t uncommon to see raw sewage floating in the lake.

“Because we were releasing our sewage. And it was having a huge effect on the ecosystem,” Fresh says. “This was back in the ‘60s and ‘70s when we didn’t know some of the things we do now. And basically we found that if we could reduce the amount of phosphorous, we could really clean the lake up.”

He says after we cleaned it up, the ecosystem came back, and the Lake Washington chinook has become a “poster child” for salmon recovery issues.

“You get the right phytoplankton, you get the right zooplankton and then you get the right things for salmon to feed on.”

So while Lake Washington chinook stands as one of the most challenged of all the threatened salmon runs in the northwest, Fresh says it’s also one of the most inspiring to see surviving and hopefully, slowly coming back, right in the middle of a heavily urbanized area.

“I couldn’t come up with a harder pace to implement recovery,” Fresh says. “I think the Endangered Species Act and its focus on chinook salmon in this area gave us one of the ultimate challenges in recovering endangered and threatened species.”

But if we can do it here, in an urban area with such a diversity of needs and uses, he says the lessons learned could pay off tremendously.

“I really believe that. If we can make it work in places like this, then I think we have the ability to take better care of our resources in other places.” Fresh says. “I think we’ve got to go for it.”

Pingback: Wednesday, October 8th "Field Trip Prep and Biomes" - Blog Biodiversity - Biodiversity and Lab Concepts - Issaquah Connect

Pingback: Part 6 Chinook Face Final Obstacle At Landsburg Dam Before Reaching ‘Shangri La’ - Swimming Upstream